If you drive across the hills of northern California, just north of San Francisco, there, across the vineyards, you’ll see a strange sight—tiny dolls’ houses, 8-9 feet high, barely bigger than a kennel, houses in miniature, but with enough space inside for a normal-sized American couple. A wooden room contains all domestic requirements: a living area that converts to a bedroom at night, a wall that hides a kitchenette and toilet, and even a tiny front porch for long evenings gazing out to a Pacific sunset. Placed among the emerald green slopes of the valley and across gentle ridges, the sight of these miniature structures seems exceptionally misplaced in a country that has long valued bigness—big houses, big cars, big estates, skyscrapers, long-span bridges, big highways. Suddenly, in a big country, things are small, compact, manageable and made with an eye to the future.

Compare that with a drive into the hills of Uttarakhand, to Mukteshwar and Ramgarh. Across forests freshly cut, on high ridges, you will see, not one, but multiples of 10—20, even 30 bungalows—spread cheek by jowl, on high ground. Each has four bedrooms, with attached baths, living, dining, separate servant’s quarters, garage and service space, what builders describe as 4BHK—a replication of city life on the mountains. Each built on the principle of bigness, and displaying an attitude of utter contempt for efficiency, utility and the surrounding ecology. Big, brash, unmanageable and outmoded may not be mentioned on the brochure to procure their sale, but their presence on once wooded and agricultural mountain land only magnifies the desolation. Do such places have a future in a country that has for so long neglected its ecology, architectural traditions and available technology? What does the Indian house say about the places we make for ourselves, the poverty of spirit and the call to social and civic disorder? Is it enough to let out a howl, and then put a downpayment on the same bungalows…

The reach of architecture is embedded as much in daily crisis as in the uplifting of our spirit. Every new house built, every new brick planted on a building site, is a signal of hope. The future is always meant to be better; architecture makes such a monumental, visual and environmental impact, its basis has to be rooted in perennial optimism. Yet, one of the many drawbacks of current architectural practice is the absence of a constructed subversion—the hope that the vision for a future house could be different and filled with new possibility.

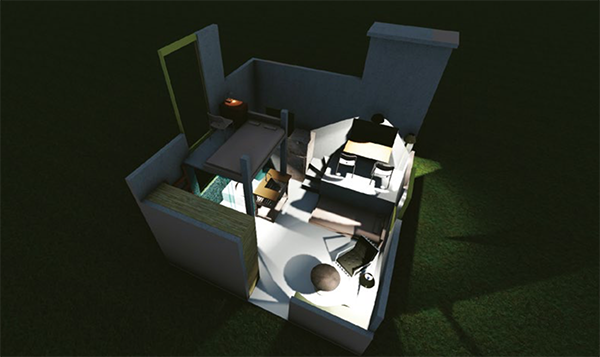

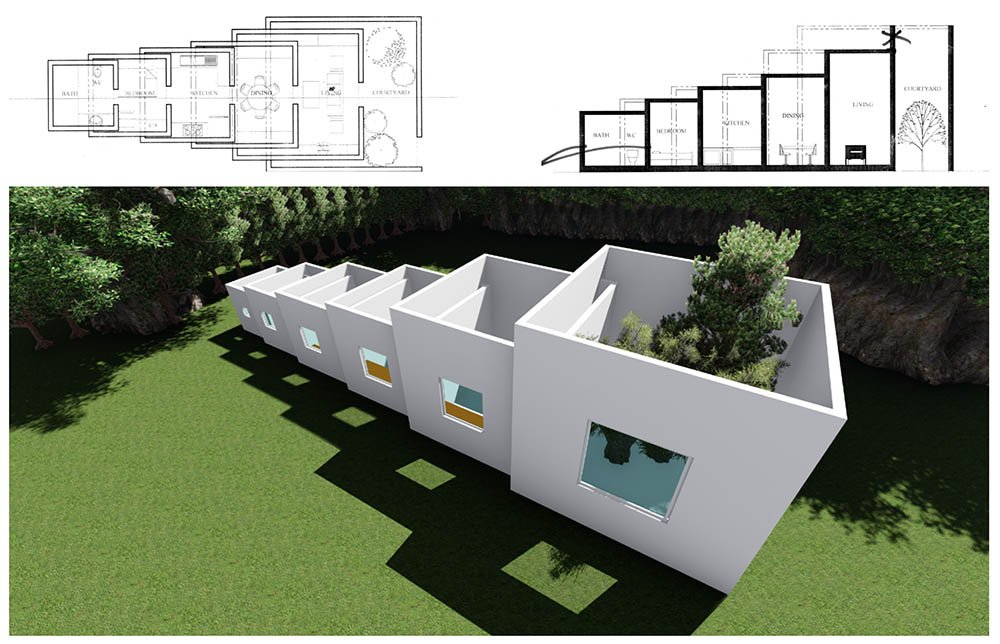

To fill the gap I have long felt the need to create an imaginary perspective of architectural ideals—driving domestic ideas out of the necessity of mere functional performance into the magnified imaginary logic of oblique and untested ideas. Could an earth house, embedded deep below ground, provide a collective of insulated rooms around a sunken courtyard? Could a single room make living, eating, sleeping possible within a compressed space where functions are released and retracted into the wall— a multi-level five-metre cube that could accommodate a whole family, like a Japanese apartment? Could the home expand—like an accordion—with the growth of the family, enlarging and contracting as required? Could, in fact, a “globe house”, suspended in the atmosphere, do away with the need for land?

I had believed in such compaction long enough to think that its translation into real life was a distinct possibility. So the plans come, black lines on paper, 3Ds set convincingly in landscape, dimensioned working drawings that set the idea firmly in black and white. But that is all. Without the support of the client, the builder, the bureaucrat, they remain in an office drawing file marked “Future Buildings”.

Obviously, the untested and often extreme view of some of these ideas may appear farcical at first, but the position becomes less radical when seen against the backdrop of the country’s own extremes. The extreme state of poverty and a history of Western hand-me-downs itself encourages a radical position. The unimaginably wide disparities in living conditions must force imaginative Indian cultural solutions. It is what a magician describes as “creative imbalance”, working on the edge of getting your secret discovered, the hope that an audience pins on the failure of an impossible high-wire act. When it fails it is serious tragedy—and comedy. When it succeeds, it crosses an unknown frontier…

***

Published earlier in the Indian Quarterly, this article has been reproduced with permission.